As St. Patrick’s Day Approaches, Americans Ask: Am I Irish?

DUBLIN, IRELAND (March 8, 2025) — If you have to ask, the answer is no. Let me break it down for those who wonder why not.

My mother’s parents emigrated from County Meath (her father) and County Limerick (her mother) one hundred years ago. Decades later, when my maternal grandparents were both alive, I relied on them for the documents needed for me to be entered in the Foreign Births Register (FBR) and thus obtain Irish citizenship through the Irish Department of Foreign Affairs, which oversees citizenship applications. Although my memory is hazy, I recall that between starting the process and getting an Irish/European Union passport took about 18 months and cost about $200.

In 2023, I moved to Dublin, which means I am an Irish citizen, now resident in Ireland, having the same rights and obligations as any other Irish citizen in the Republic — to work, to vote, to serve on a jury. I am not a tourist.

So, am I Irish?

That would still be a no.

No matter how many pints of Guinness at Temple Bar, no matter how many trad sessions at the Cobblestone, no matter how many times I waive a camán (hurl) at a sliotar, or watch The Quiet Man, I am not now nor will I ever be Irish. I am an American with Irish citizenship living in Dublin.

There is a saying — or more an example of collective Irish bravado: there are two kinds of people in the world, those who are Irish and those who wish they were.

My father, who passed away several years ago, was among the latter. He graduated from the University of Notre Dame. He was an avid follower of the Fighting Irish football team. As an attorney, he once had the Irish Development Agency as a client. He traveled extensively in Ireland, occasionally visiting with my mother’s extended family. He very much wanted to be Irish. He never corrected anyone’s impression if they got the idea (from him) that he was full-blooded Irish. His actual background was half English/Scottish (paternal) and half Italian/Czech (maternal).

My mother recently passed away. I returned to the United States for the funeral. My mom was the seventh of nine children, six girls and three boys. Two of her remaining brothers jokingly remarked that after going on two years in Ireland, I was not speaking with a brogue. I told them I never would.

If anyone asks about me here — and they so often do once they hear my decidedly non-Dublin accent — I would never say “I’m Irish”.

Because I am asked these sorts of questions so often, I have come up with a considered reply as my default response: “I am from New York but live here now. I have the Irish citizenship through my mother’s parents, who were from Limerick and Meath.”

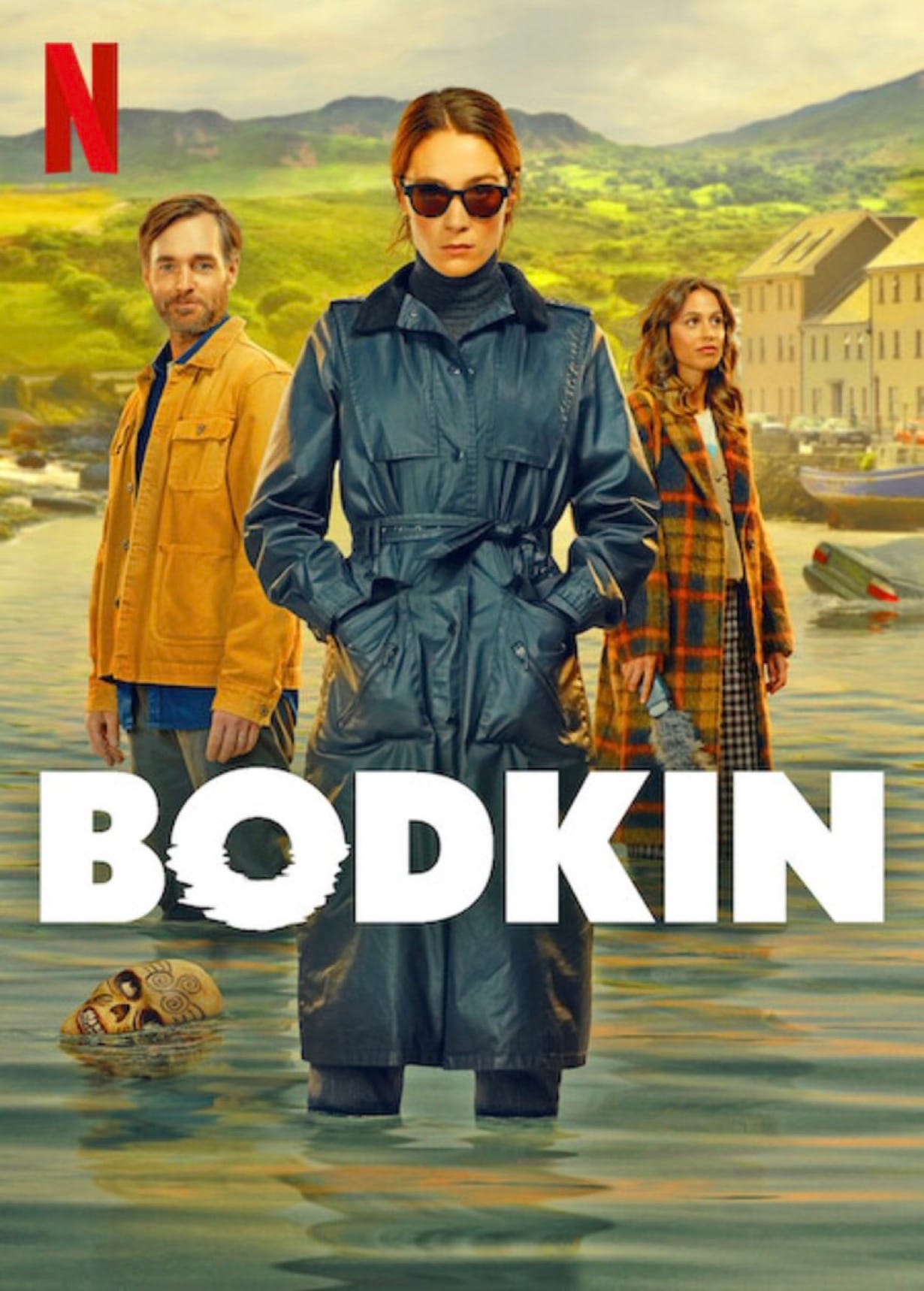

There is a fantastic scene that addresses this phenomenon in the wonderful Netflix series Bodkin which follows a group of podcasters—Gilbert Power (Will Forte), Dove Maloney (Siobhán Cullen), and Emmy Sizergh (Robyn Cara)—as they head to a fictional Irish town called Bodkin to investigate the mysterious disappearance of three people from decades ago during the Samhain festival or as Gilbert calls it “Irish Halloween”. Like most things about Ireland, he had it the wrong way around.

That Gilbert is making a podcast about a disappearance of people during a past Samhain while attending a corporate-funded revival of Samhain in the town is central to the broader theme of the series. Samhain is Halloween’s ancestor, carried from Ireland’s Celtic past to America via immigration, transformed by Christianization, cultural fusion, and commercialization. Samhain (pronounced "SAH-win" or "SOW-in"), the precursor to Halloween, is an ancient Celtic harvest festival in Ireland that dates back 2,000 years. Samhain took place on or about October 31 and was seen as a time when the boundary between the living world and the "Otherworld" thinned, making it a night for honoring the dead, divination, and protecting against mischievous spirits.

When Christianity spread to Ireland by the 5th century, the Church sought to overlay pagan festivals with Christian ones. In the 8th century, Pope Gregory III established All Saints’ Day on November 1, likely to co-opt Samhain. The night before became All Hallows’ Eve, eventually shortened to "Halloween”. The link to modern American Halloween solidified in the 19th century during the Great Famine (1845-1852) when over a million Irish immigrants fled to the U.S. They brought Samhain traditions, blending them with local customs and other immigrant influences (turnips or beets were carved with faces to repel spirits but in America replaced by pumpkins as Jack-o’-lanterns, disguising and leaving offerings evolved into Trick-or-Treating).

This dark comedy-thriller premiered on May 9, 2024 (no word from Netflix on a Season 2). What starts as a quirky true-crime podcast pitch turns into a wild, absurd unraveling of secrets involving smugglers, eels, and local eccentrics.

Filmed in stunning West Cork locations like Union Hall and nearby Glandalore, Bodkin weaves in many clever and funny jabs at how Americans are perceived by the Irish, leaning into cultural stereotypes with a satirical edge that’s both playful and pointed. The show uses its American protagonist, Gilbert Power, as the main vehicle for this humor, contrasting his starry-eyed enthusiasm with the more grounded, often sardonic Irish perspective.

Gilbert arrives in the fictional Irish town of Bodkin with a quintessential American mindset—he’s overly cheerful, assumes Ireland is a quaint, shamrock-dotted wonderland, and believes his Irish heritage (however distant) gives him an instant connection to the place. This is a classic trope of the "plastic Paddy"—an American who romanticizes Ireland based on clichés like Guinness, leprechauns, and a misty-eyed view of the "old country." The Irish characters, particularly Dove, see right through this. Dove, a sharp-tongued, Dublin-born journalist, calls him out early on, sneering that he “thinks rural Ireland is Disneyland.” Her disdain reflects a common Irish perception of Americans as naive tourists who reduce their culture to a postcard fantasy, ignoring the real complexities of modern Ireland.

The show milks this dynamic for laughs in subtle and overt ways. For instance, Gilbert’s wide-eyed awe at things like road bowling—a traditional Irish sport—or a nun in a pub (which he finds delightfully exotic) is met with eye-rolls or bemusement from the locals, who treat these as mundane. There’s a scene where he’s pitched touristy nonsense by the townsfolk, and he laps it up, oblivious to their sly mockery. It’s a nod to how some Irish might see Americans as gullible, easily sold on a caricatured version of their identity. The locals even play into his expectations at times, exaggerating their "Oirishness" (think diddly-dee music and folksy charm) to mess with him, revealing a quiet amusement at his expense.

Dove embodies a prickly Irish skepticism that clashes with Gilbert’s can-do optimism, highlighting a cultural divide where Americans are seen as loud, earnest, and a bit full of themselves, while the Irish pride themselves on being more reserved and self-aware.

The humor also extends to how Gilbert’s American-ness sticks out in Bodkin. His loud friendliness and tendency to overshare contrast with the town’s guarded, tight-lipped vibe. The Irish characters often respond with dry wit or outright dismissal, poking fun at his inability to read the room. It’s not mean-spirited, but it underscores a perception of Americans as overly performative and unfamiliar with the subtleties of Irish social cues.

It’s less about malice and more about the Irish teasing out the absurdity of how Americans—through Gilbert—project their narrative onto Ireland. The show balances this with enough quirks (eels, nuns, and all) to keep it from feeling one-sided, but the laughs at Gilbert’s expense are a standout thread.

Gilbert’s American optimism and tendency to fetishize Ireland are the punchline, while the Irish characters—Dove especially—use wit and skepticism to expose the absurdity. It’s less about hostility and more about the locals watching this loud Yank bumble through their world, amused at how he doesn’t quite get it.

A recap from The Irish Times notes Gilbert “prattling on about his Cork roots”. Pub scenes, like one in Episode 1 where he chats with Seamus Gallagher (David Wilmot), are key for appreciating mischievous local interactions.

At a “real” pub (loud rock music, no nuns at the bar sipping a pint, no trad music) — not a “tourist-trap of a pub” as a snarling Dove puts it — Gilbert is approached by Seamus who wants to meet the American podcaster everyone is talking about. Gilbert is excited to be recognized and proudly tells Seamus he’s Irish that his great-grandfather was Michael Power from Cork (they are in County Cork). The scene, and the juxtaposition of the “tourist” pub and the “real” pub, sets up an exchange that perhaps best illustrates Bodkin’s take on Americans visiting Ireland.

Seamus: I hear we have an American podcaster in town.

Gilbert: Yes, sir, but actually, I'm Irish. Gilbert Power.

Seamus: Seamus Gallagher. You’re Irish, are you?

Gilbert: Uh huh.

Seamus: You don't say.

Gilbert: I do say. Yeah, my great-grandfather was Michael Power, from Cork

Seamus: Michael Power?

Gilbert: Yes, sir.

Seamus: Cork, you say?

Gilbert: Yeah

Seamus: That would make us mortal enemies.

Gilbert: What?

Seamus: Your great-grandfather was a thief, and he stole five acres of land from my great-grandfather. Now I'm gonna have to ask you to leave before things get ugly.

Gilbert: Umm uh. First of all, I'm sorry, I didn't even… umm… generations… uh…

Seamus: I’m messing with ya, Gilbert Power. Come on now. I’ll buy you a drink, and I’ll introduce you to the lads.

Gilbert is relieved, and happy to join Seamus to “meet the lads”, unaware that this is a set-up. Seamus is not a good person. Gilbert will be plied with whiskey to the point he has no memory of losing €8,000 playing darts (the wager is helpfully recorded for him on one of the lad’s iPhone).

Some folks involved in creating Bodkin have a keen ear for this sardonic teasing of Americans re-connecting to their Irish roots. Bodkin was created by British writer Jez Scharf, who led a team of writers that included Alex Metcalf, Oneika Barrett, Paddy Campbell, Megan Mostyn-Brown, Mike O'Leary, and Ursula Rani Sarma. On the production side, Scharf and Metcalf were joined as executive producers by Tonia Davis, Barack, and Michelle Obama through their Higher Ground production company, David Flynn and Paul Lee for wiip, and Nne Ebong for Netflix. Nash Edgerton, who also directed some episodes, is listed as an executive producer as well. The series’ creative team also included directors Bronwen Hughes, Johnny Allan, Paddy Breathnach, and Nash Edgerton.

Two of the writers and producers of Bodkin might have had a strong sense of Irish disdain for American tourists seeking their roots, particularly through the lens of Gilbert, an American podcaster from Chicago, who comes to Ireland to investigate a mystery while naively trying to connect with their Irish heritage. This theme is central to the show’s humor, as the Irish locals often view these outsiders with a mix of amusement and irritation—a dynamic that requires a nuanced understanding of Irish culture and its perception of American tourists.

My sense is Among the writers and producers, Ursula Rani Sarma is the most likely to have a deep, authentic sense of Irish disdain for American tourists connecting to their roots. Her background as an Irish playwright from Cork, combined with her experience writing about Irish identity, positions her as someone who would naturally understand and portray the local perspective in Bodkin. She likely contributed to the sharp, humorous jabs at characters like Gilbert, capturing the Irish locals’ bemusement and irritation with cultural accuracy. Paddy Campbell and David Flynn, both Irish, also likely had a good sense of this dynamic and may have supported Sarma in ensuring the show’s portrayal felt genuine.

I do not actually know this to be the case, so if I have it wrong please let me know but Sarma’s direct connection to Cork and her extensive work on Irish themes make her the most likely candidate. Writers like Scharf and Metcalf, while instrumental in shaping the overall narrative, probably relied on Sarma, Campbell, and Flynn to infuse the script with authentic Irish sentiment.

Whoever wrote the pub scene and the rest, the message to American’s visiting Ireland is clear: come and enjoy, it’s lovely and fun, but don’t be a Gilbert.