What Scandinavian Crime Fiction Can Tell Us About Police Reform in America

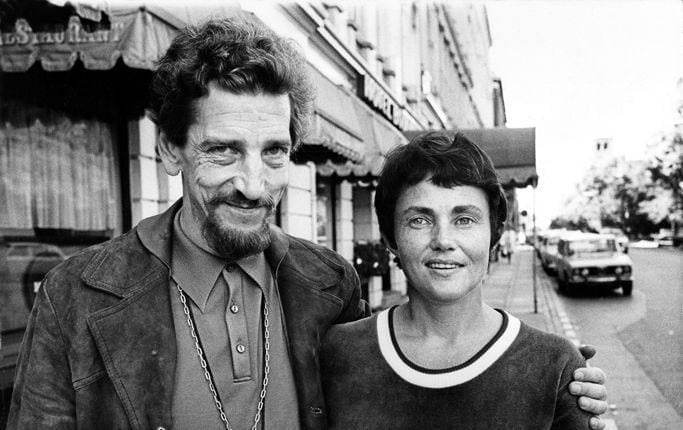

Maj Sjöwall and Per Wahlöö have a few thoughts on the self-image of police officers

Over the past few years, I have become a fan of Nordic Noir, also known as Scandinavian Noir, a genre of crime fiction set in Scandinavia or Nordic countries (Sweden, Norway, Finland, Denmark, Iceland).

Nordic Noir is described as “Plain language avoiding metaphor and set in bleak landscapes results in a dark and morally complex mood, depicting a tension between the apparently still and bland social surface and the murder, misogyny, rape, and racism it depicts as lying underneath”.

Popular Nordic Noir novels haven been turned into popular TV series — The Killing (Denmark), The Bridge (Denmark-Sweden), Trapped (Iceland) and Sorjonen, aka Bordertown (Finland) — and reached new audiences thanks to subtitles on Netflix, Amazon Prime and the BBC.

The Martin Beck series of novels by Maj Sjöwall and Per Wahlöö were among the first to stake out this new genre, influenced by the American writer Ed McBain (who is cited in the series by name).

Sjöwall and Wahlöö “realized that there was a huge unexplored territory in which crime novels could form the framework for stories containing social criticism”.

The Abominable Man is a 1971 police procedural novel by Maj Sjöwall and Per Wahlöö. It is the seventh book in their series about Martin Beck in which the National Murder Squad, led by Beck, attempts to solve the brutal murder of a senior police commander known, in turn, for his brutality.

Within the social commentary in the book is a discussion about sociologists and their despised (by the police) insistence on writing reports for the Stockholm Police Department about their police officers.

In The Abominable Man, Sjöwall and Wahlöö write:

“The police force took a very dim view of sociologists — particularly in recent years since they'd started focusing more and more on the activities and attitudes of policemen — and all their pronouncements were read with great suspicion by the men at the top. Perhaps the brass realized that in the long run it would prove untenable simply to insist that everyone involved in sociology was actually a communist or some other subversive.”

By the time of this seventh novel in the series, the main character has moved up from Detective to Inspector, and Chief of the National Murder Squad. As part of senior command, he is more than ever confronted by political and social issues beyond simply solving murders. In The Abominable Man, he is carrying a copy of the latest sociologists’ report which was left on his desk. It is in his pocket to signify he, a senior commander, has not read the report, so the narrator is left to explain the report to the reader.

“The report in Martin Beck's pocket revealed a number of interesting new facts. It proved that police work wasn't a bit more dangerous than any other profession. On the contrary, most other jobs involved much greater risks. Construction workers and lumberjacks lived considerably more hazardous lives, not to mention dockers or taxi drivers or housewives.

But hadn't it always been generally accepted that a policeman's lot was riskier and tougher and less well paid than any other? The answer was painfully simple. Yes, but only because no other professional group suffered from such role fixation or dramatized its daily life to the same degree as did the police.”

The narrator continues:

“The number of injured policemen was negligible when compared with the number of people annually mistreated by the police. It's not dangerous to be a policeman, and in fact it's the policemen who are dangerous”.

Police Killed Over 1,000 American Civilians In 2019

This got me wondering if what was true in Sweden in the early 70s about the risk of being a police officer is true in the United States today. Turns out it is almost the same.

The United States Bureau of Labor Statistics compiles annual data on fatal work injuries by job classification and issues an annual report.

Fatal occupational injuries by occupation and event or exposure, all United States, 2019

There were 5,333 fatal work injuries recorded in the United States in 2019, a 2 percent increase from the 5,250 in 2018, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. The 5,333 fatal occupational injuries in 2019 represents the largest annual number since 2007.

The most common workplace deaths were related to transportation. Driver/sales workers and truck drivers incurred 1,005 fatal occupational injuries, the highest since the series began in 2003.

Fatalities in the private construction industry increased 5 percent to 1,061–the largest total since 2007.

Fatal occupational injuries among law enforcement workers fell 24 percent between 2018 and 2019 (from 127 to 97) of which 42 were transportation incidents and 57 were violence by persons, self-inflicted injury (suicide), and attacks by animals. Four dozen police officers were killed by another person in 2019.

FBI Releases 2019 Statistics on Law Enforcement Officers Killed in the Line of Duty

While the hope is that no one is ever killed on the job including if not especially police officers, Sjöwall and Wahlöö speculate as to why it is generally accepted that the job of police officer is riskier than other jobs when it is not and never has been.

“If you really want to be sure of getting caught, the thing to do is kill a policeman. This truth applies in most places and especially in Sweden. There are plenty of unsolved murders in Swedish criminal history, but not one of them involves the murder of a policeman.

When a member of their own troop meets with misfortune, the police seem to acquire many times their usual energy. All the complaints about lack of manpower and resources stop, and suddenly it's possible to mobilize several hundred men for an investigation that would normally have occupied no more than three or four. A man who lays hands on a policeman always gets caught not because the general public takes a solid stand behind the forces of law and order — as it does, for example, in England or the socialist countries — but because the police chief's entire private army suddenly knows what it wants, and, what's more, wants it very badly.”

In other words, it is the police departments themselves that project the idea that police work is the riskiest job — amplified by news media, talk radio, and Hollywood — because it suits them to do so.

The BLS report contains extensive data on fatal work injury rates per 100,000 full-time equivalent workers by selected occupations, 2019 along with a chart of the top 10 most dangerous occupations by fatalities per 100,000.

- Fishing and hunting workers (145.0)

- Logging workers (68.9)

- Aircraft pilots and flight engineers (68.1)

- Roofers (54.0)

- Helpers, construction trades (40.0)

- Refuse and recyclable material collectors (35.2)

- Driver/sales workers and truck drivers (26.8)

- Structural iron and steelworkers (26.3)

- Farmers, ranchers, and other agricultural managers (23.2)

- Grounds maintenance workers (23.2)

Below them on the BLS list are supervisors of construction trades and extraction workers, construction laborers, supervisors of mechanics, installers, and repairers, extraction workers, maintenance and repair workers, general, electrical power-line installers and repairers, operating engineers and other construction equipment operators, supervisors of landscaping, lawn service, and groundskeeping workers.

Police and sheriff's patrol officers enter the list ranked #20 with 11.1 fatalities per 100,000, slightly above taxi drivers, carpenters, bus and truck mechanics and painters. And most of those 11.1 fatalities are related to driving a police vehicle (i.e., fatal collisions).

For those wondering, Firefighters and Paramedics did not make the BLS list of fatalities per 100,000. 24 Firefighters died on the job, 9 of them due to “transportation”; 8 EMTs/Paramedics died on the job, 6 of them due to “transportation”.

By contrast, 20 school crossing guards/flaggers died on the job.

Why does it matter if police work is or is not more dangerous than other jobs?

Mainly because the idea that police work carries more risk than any other job is used to justify all manner of bad behavior such as police brutality, suicide, misogyny, racism, homophobia or engaging in illegal behavior such as theft, time theft and so on.

You do not often hear that it is appropriate for a sanitation worker to punch a homeowner in the nose because they did not properly sort their recycling and yet, you can often hear this exact justification used if a suspect fled police or was otherwise uncooperative.

It is why there are plenty of people today who believe “backing the blue” translates into condoning, even cheerleading, for Rodney King Justice.

The BLS stats show that among job classification for a municipal workforce like New Rochelle it is far more dangerous to work for the Department of Public Works or Parks & Recreation than the Police Department.

Over at the Board of Education, the Buildings & Grounds staff and other Service Related Professionals are at far greater risk than Pedagogical Staff such as teachers and school administrators. Among preschool, elementary, middle, secondary, and special education teachers, 5 died, 3 of them due to slips and falls.

Recognizing the data clashes with the self-image of many police officers and their sycophants and servile, self-seeking flatterers, we would point them to the Bureau of Labor Statistics which clearly show that people working construction jobs to build new housing or driving delivery trucks to supply grocery stores and gas stations are at far greater risk of being killed on the job than police officers.